Why does the question of civilization's point of origin still burn? We sense that a large chunk of the story is missing, that we are that foundling brought up a pauper in ignorance of his royal heritage: prince Pryderi brought up as a stable hand, Jack in the Green as a chimney- sweep, Daphnis a goatherd. Open up the coffers of our past, we cry, let us have our birthright. And so when we get on the trail of something major that we sense is stalking the prehistoric territories just beyond the borders of the known, it is a massive spur to our curiosity.

Walking the streets of Aix-en-Provence on this sweltering June morning it might seem a little over the top to speak of cultural paucity. Even without the lost civilization, a great richness is apparent. A French market fills a square, natural spring-water gushes from a fountain in the shape of a sanglier, a wild boar, warm breezes waft through the shade of streets lined with late Renaissance sandstone buildings, and cicadas chirp in the trees of walled gardens. Kate is a Picasso fan; I have a certain fascination with Cezanne, so a trip to the Granet Museum to see an exhibition themed on Cezanne's influence on Picasso, and Picasso's idolization of Cezanne, seemed like a good plan. Picasso, drawn by the motif of his hero, a pilgrim drawn to a sacred icon, lived for a while at the foot of Monte Sainte-Victoire, the limestone massif that rises east of Aix, and he is buried there. The estate Picasso bought included part of the mountain.

"I've bought Cezanne's Sainte-Victoire," the Spanish-born painter boasted.

He was asked in reply which one, for Cezanne had painted the mountain many times.

"The real thing," was his proud reply.

The cultural richness of the area is evident as we walk on from the part of the museum devoted to the exhibition and into the part that contains the fine classical paintings of Granet, several of these being portraits of the Aix mountain, Sainte-Victoire, which the artist liked to show framed by an arch, door or window. I notice one among these that is something of a curiosity. Granet painted a Death of Poussin, showing the great French-born, Rome-based master on his death bed. Hanging above the bed on the wall in Granet's painting is an image of one of Poussin's own paintings, thought by many to be a meditation on mortality, The Shepherds of Arcadia II. There is a difference, however. The mountain behind the tomb is raised up higher on the horizon, the reason being, it has been suggested, that this allowed the Aixoise Granet to assert through the more visible leonine profile of the mountain that it is in fact Sainte-Victoire.

Visiting Cezanne's atelier in Aix, his studio kept just as it was, one may observe that he had a print of this same Poussin painting on his wall, The Shepherds of Arcadia II. The theme is Virgil-esque; the Shepherds painting is effectively an updating of an earlier illustration to the Roman poet's pastoral poems, his eclogues. Inspired by the fifth eclogue, Poussin shows Arcadian shepherds who have built a shrine like the one in the poem built to honour the death and ascension into the starry heavens of Daphnis, the ideal shepherd, probably as the ideal shepherd constellation, Bootes, who was identified by some (such as Hyginus) with the legendary ancestor of the Arcadians. (Indeed it has been pointed out that the figure in the Poussin with one foot on a rock references Bootes, who by the 17th century was shown on constellation charts with one foot on a rock that was named after Mainalos, the mountain in Arcadia in southern Greece that is sacred to Pan. The kneeling, pointing, bearded shepherd next to him in the painting confirms this, for he works as the nearby constellation of Hercules, the Kneeling Man.) As a young man Cezanne, though now called the Father of Modern Art, walked the countryside around Aix with friends reading Virgil's eclogues, no doubt conceiving of the Provencal landscape in these classical terms.

And here we have an instance of the way that all the known, the historic civilizations remain haunted by the prehistoric: the Arcadia in question stands for the Old Culture, the Golden Age of herders before bronze and iron weapons, before the Earth was torn by the plough.

We walked on past post-Renaissance classical statues in another hall in the Granet Museum.

"Who's that?" Kate asks, pointing to a maiden whose foot is being bitten by a serpent. I point to the nearby statue of Orpheus and briefly explain the myth, how he could have brought Euridice back from the Underworld if he hadn't looked back to check she was there.

We walk on into the next room and see a collection of Greek amphorae, urns, dishes and other pottery. These are evidence of the wine trade in the Aix area, and of the close proximity of Marseilles, a city of ancient Greek settlers for several hundred years. The Romans too had an obvious presence in this region – the name Provence denotes that this was as Roman province, and Aix was a Roman city with baths fed by the springs. Yesterday we visited the Roman temple behind the winery at Chateaux Bas in the countryside north of Aix, looking delicious in the evening Sun, something out of a Claude Loraine pastoral idyll in oil, (and now I imbibe the produce of this local vineyard as I write).

But the cultural richness in this area doesn't extinguish my curiosity about the older culture; rather it acts as a big signpost, an arrow pointing fervently at Arcadia. Almost every subsequent culture, every stage of art, Modern Art included, has been haunted by this older culture. Even Picasso, the leading figure of Modern Art, was interested in "primitive" art and went through his phase of painting fauns playing pipes, and minotaurs, and the arrow points on back through the Bacchanals of Poussin, to Poussin's inspiration, Titian, and other Renaissance masters, back to classical antiquity of course, where these half-human half-animal characters stalk the stone stages and the stories. Even today when I look into the shaded rocky woodland of the sunny South, the pine-clad slopes of these ancient hills, I continually expect to see a satyr dance from shadow to shadow. But the arrow points back to a time earlier even than classical antiquity, for the cave paintings of the Old Culture here in France show us a bison-headed man – a minotaur – and also a silenus, for the so-called Dancing Sorcerer cave painting has the tail, mane and quite possibly the genitals of a horse, just as do the silenoi that frolic through the art and myths of Ancient Greece. What was this older culture where shamans or totemites would don such costumes, the civilization which predated yet lasted more than three times as long as the full four thousand years of pharaonic Egypt, and the fertile ground out of which has sprouted all that has followed in Western Culture? This is the great mystery.

Devereux's Answer

How does one begin to make headway when looking for ways to access the mindset of the ancients? How can we begin to see with the eyes of the Lost Civilization, to recover their treasure, the Arcadian Dreamtime? Paul Devereux, an inspired and prolific writer on the subject of Earth Mysteries, asked this question of how to find the sacred sites of the ancients and the way that they viewed them, and proposed an answer based on the collation of great tracts of anthropological research. In The Sacred Place he describes how studies of many cultures on every continent have shown certain commonalities between places considered sacred. Indeed, he suggests that even where a tradition has been lost, we can make an educated guess that a site was considered sacred if (1) a lasting landscape form presents an intelligible shape, with a further category involving (2) slight enhancement of this simulacrum by human action, and with a third category being those having (3) some significant alignment to the heavens. Why should these features be so perennially and trans-culturally effective? Such universal ideas allow for a tuning into what Devereux calls "the imprint of the ancestors", and the work of biologist Rupert Sheldrake has shown that claims of the existence of such a phenomenon – the "presence of the past" – can be backed up with empirical support, suggesting that the Dreamtime of a sacred landscape feature actually exists as a culturally enriching morphic field.

The existence and preservation of ancient artefacts and sacred sites is a perfect record of …[human] curiosities and passions [over the ages]. Your heart expands because the beauty held in form through time by caring humans centers you in 3D and expands via 6D morphic fields. You tingle and feel awestruck….This helps you to feel that you are free, that you are in harmony. –

An irregular form suggesting something different (or nothing much in particular) to each individual viewer does not establish a strong collective field, for resonance relies on similarity. Just as sonic resonance occurs between strings of the same length or in harmonic ratio, as with the resonating un-plucked strings on a sitar, mental resonance is activated, across time, by similarity of idea. All thoughts about chairs have a certain similarity of definition, and that core essence of similarity is the Platonic Form of all chairs, call it if you like the Throne of Osiris, and associate it if you like with the Cassiopeia constellation. When we see the Universal within the Particular, a still life of a something like chair can be an iridescent, transcendent, angelic symphony, because of resonance. If there is no similarity of idea about how a landscape is perceived, then it will not receiving the vivifying influx of the Realm of Collective Ideas. You may get a virtuoso solo line in the present, but you won't get the harmony and magnificence of a great symphony reverberating across time. Narcissus would lose his Echo, the ancestors would fall dumb, and the sitar's spell would be broken. Conversely, where a lasting landscape form does look like some universally recognisable form, and this is honoured, the area develops an aura, a mist, a field which is called the Dreamtime. Where such natural forms are lacking or could do with a helping hand, enduring stone buildings can be erected which embody the most definable – and thus resonant – of all spatial forms, those of sacred geometry, and such buildings are called temples. So the site is consecrated and the aura develops. Why Category 3 – alignment to the heavens? The constellations are very ancient forms, visible to all, and grounding them into a site is therefore an act of alchemy, infusing this imprinted richness into the sense of place – Hancock's "Heaven's Mirror". And if this theory is true, as I strongly believe it is, then the notion that we would ever be so "modern" as to outgrow either the old myths of the landscape, or for that matter the brilliant classical traditions of architecture, such a notion is revealed as preposterous. We are all aborigines, fitting into two categories: those that have and those that haven't become dispossessed of our totems.

Any object…is held in form by the morphic field of that object…. Many artists can see such fields, and the visual arts strive to make these fields visible, since they are actually the source of beauty in matter.

Beauty and desire are what cause things to come into existence in the first place, and a painter can make this visible….When an artist strives for true beauty, these fields can actually be felt and heard. –

Continuing to the final room of the museum we see the rather more simplistic carvings of the Celto-Ligurian people who had a capital at Aix before the Romans arrived. They had their settlement upon on a hill overlooking Monte Sainte-Victoire, the mountain which they held sacred to their god of the wind, of the mistral, Vintour. So the god was envisioned solidified in mountainous form.

Kurunba [numinosity] is a metaphysical [Aboriginal] expression denoting the presence of a cultural layer within the landscape form itself that has been inspired by mythological contact with the Dreaming. –

The Cave Painters of Old Europe – Morphological Accuracy and Abilities as Climbers

We have invented nothing. –

Painting, whether on cave walls or bark shelters, is one of the ways in which the order of the Dreaming is presented to humans [in Australian Aboriginal culture]. Another way is through their observation of the landscape itself, created as it was through ancestral activity. –

Executing and maintaining rock painting was a key part of the ambit of rituals and responsibilities vested in those responsible for particular sites – an inseparable component of the cycle of myths, songs, and rituals through which Aborigines interpret, invoke and harness the powers of their physical and spiritual environment….Painting skills, subject matter and clan designs were handed down patrilineally as a type of apprenticeship, with degrees of symbolism and subject matter deepening with advancing age and respective stages of initiation. –

This summer at the historic Provencal village of Les Baux as part of the Picasso festival there are to be projections of his paintings onto the interior walls of a large cave for public viewing. I can't help feeling that Picasso himself would have approved. He had an interest in early art including that of the Cave Painters, and he shared their love of paintings of bulls.

There is an extent to which the degree of civilization can be measured by a society's art. In other words, where there is fine art, there must also be civilization. Much of the artwork from the prehistoric caves is fine indeed. There was a civilization in Europe which maintained its artistic traditions for many thousands of years. This is our Elder Culture. We are orphaned amnesiac foundlings if we don't integrate this long tradition into our cultural understanding of ourselves. If warfare took place at all, it was not deemed important enough to be represented in any of the art. The vast majority of the images are devoted to animals. Witness the skill in this extremely old art shown here from the Chauvet Cave in southern France, depicting the foreparts of lions and bears. These artists are capable of close observation and accurate depiction of the morphology of the fauna around them. The majority of us would have to adopt the role of novice by comparison, standing as humble apprentice quietly watching while a wise-looking elder teaches us his art and the Tradition through demonstration.

Some of the art they created demonstrated their skill not only in image production but also, by its location, in climbing. They must have used ropes or created scaffolds to produce some of the works to be found high up on cave walls and ceilings. This was a society that in its own harmless way had aspiration and organisation. And they were good climbers.

The Magdalenians Appreciated Simulacra

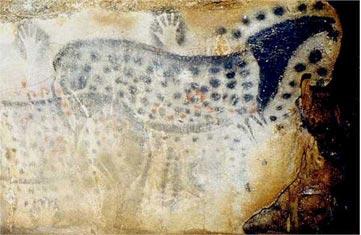

The Upper Paleolithic cave painters were appreciators of simulacra, those natural formations in rocks, trees or clouds that look like an intelligible form. There is a well-known example in one of their caves, namely Peche Merle, where a natural jutting outcrop of cave wall in the shape of a horse's head – Category 1 in Devereux's system – has been used as the starting point for a painting of a horse. This is clearly Devereux's Category 2 – the alteration and enhancement of a natural simulacrum for emphasis.

The art of Peche Merle cave is attributed to Upper Paleolithic people in the region prior to 20,000BC, known as the Gravettian Culture, while it is thought that some of the paintings in the cave may be from the period around 16,000BC onwards known as the Magdalenian. I'll be honest, I'm not fully up on all the minutiae of the differences between one European cave painter people and their descendants – they're all Arcadians to me (in the sense of ἀρχή, "very old", "original") – but it's quite obvious that traditions were handed down right across both periods. In the image above first spots were added to make a horse which had the natural horse-headed rock shape as its head, then later a smaller horse was placed over the top of this, one whose solid black neck tapers to a strangely small head inside the bigger one. It seems such things were accepted by the Gravettian/Magdalenian eye, and it gives an impression of height, as if the horse were a giant, its headed way up in the heights.

The painting of a second horse over the first has implied to archaeologists that this part of the rock wall was associated with this animal over an extended period, and, fitting with this view, the recently published (October 2008) results of uranium/thorium comparison dating work of European cave art has lead to the conclusion that individual cave art images often evolved over several thousand years. This reminds us of what we know of the Australian aboriginal rock art used for initiation into the Dreamtime. Sites were accorded a long-term mythological association, with the artworks expressing this being touched up and added to over long periods of time. The stories about these totemic ancestral figures were told to the initiate in conjunction with seeing the art at the mythologized site, and this process was treated with care and reverence because it was felt that it could have a potent effect on the consciousness of the initiate. These are Mysteries in the true Greek sense.

So, knowing that these Arcadians appreciated and honoured faunal simulacra, if we can find landscape forms in the southerly regions that escaped the ice and which have the semblance of such an intelligible form to a significant degree, we will have opened a portal to the Arcadian Dreamtime, like the wardrobe to Narnia, and indeed we shall see in a moment that our search need not be limited to subterranean regions.

The Magdalenians Were Advanced Sculptors

The cave paintings are famous, and some of the free-standing Magdalenian statuettes have also attracted attention, with good reason. In fact, some of them are stunning. On the left here is the top of a spear-thrower, with the cheeky design of an ibex (a type of goat) turning its head to view a couple of birds perched on its emerging excreta. It tells a story that was surely part of a bigger narrative. These people specialized in 3D as well as 2D representations, and we can only imagine what complex narratives they wove around their fires.

It is easier to see the light geometry of inanimate objects…because life-forms are always moving… Subtle fields are easier to see by glimpsing them with peripheral vision when they are stationary. –

The Magdalenians Sculpted Animal Forms in the Faces of Limestone Cliffs

I knew about the paintings and soon after looking further into the Magdalenian culture I came across their free-standing sculptures, but their sculpted reliefs on open limestone cliffs long remained hidden from my awareness. This part of their work is, I feel, highly significant, and it busts the myth that the only remains of their culture are to be found in long-sealed off underground caverns.

In Cap Blanc, in the same region as the amazing Lascaux caves, i.e. the Dordogne, there is a limestone cliff onto which were carved images of horses, bison and reindeer, around 15,000 years ago. Some of these carvings are as much as two metres long, and the total amount of sculpting work at Cap Blanc is considerable, and particularly impressive when you bear in mind the tools they were using. When the area was first excavated several typical Magdalenian tools were found, along with large stone objects which archaeologists are confident were of the type that had been used to carve these figures out of the rock. Clearly they were sufficiently committed to their artwork to labour for long hours to produce these animal reliefs in the rocky cliff-face, and they knew how to do so with precision.

Magdalenian horse sculpted into a limestone cliff at Cap Blanc, France

There is a Magdalenian Cave in the South Face of Sainte-Victoire

I once read in a local guide book that there is a cave up in the side of Sainte-Victoire which "shows evidence of Magdalenian cultic ritual."For a while I was frustrated while trying to recall where I had read this, but then I obtained more information from reading another book, Sainte-Victoire Cezanne 1990, produced by the Granet museum in Aix in conjunction with one of their exhibitions. From this I have learnt that the cave in question is La Grotte du Petit Chanteur, and that it is located half-way up the southern slope, at an altitude of about 700m, and that it was found to contain flint tools such as burins (stone chisels used for engraving stone and bone) and vestiges of fauna such as ibex and chamois, which a certain G.Onoratini attributes to the Upper Magdalenians, who occupied regions to the west of here but are attested elsewhere this far east into Provence.

Why "cultic ritual" in the lost guide? Well I suppose several hundred metres of precipitous rock face would have been a hell of a long way to climb every time they wanted to pop out to the local epicerie and back. In other words, it's unlikely that they used the cave as a living space. Their activities in this cave must have had some motive beyond the everyday.

So here they were in a cave on the south face of these limestone cliffs with tools used for engraving stone…did they leave here any of their reliefs of animal forms, as at Cap Blanc? Did they find in the form of the mountain any simulacra that they could honour or even enhance?

Sainte-Victoire as Category 1 Sacred Site : the Natural Simulacrum

The form of the Sainte-Victoire massif is complex and very different shapes are seen when looking from different angles. The one that is of particular interest here is that which is seen when we are to the west of the mountain, looking east. Shown here is an image of this view in a photograph taken by myself on a September evening from the spot on the hill of Les Lauves where Cezanne liked to set up his easel.

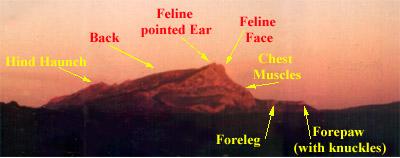

Remembering that small-headedness can be a feature of the animals depicted by the Cave Painters, this seems to me to be an elegant simulacrum of a lion in the classic sphinx pose, and indeed that the profile is leonine had been suggested already before I came on the scene. For clarification, this following image shows how the simulacrum works for me:

It is a pose that lions will assume naturally. Lions lived in this region at the same time as the Magdalenians. The people painted these animals' portraits in the caves, as we have seen. They appreciated simulacra, as we have also seen. The leonine profile cannot have escaped their attention, and their rituals must have imprinted the fields of this form.

One of several Cezanne paintings of Sainte Victoire in Sphinx profile

"Look at Sainte-Victoire there. What aliveness, how imperiously it thirsts for the sun!…[But when not illuminated]…all its weight sinks back….Those blocks were once fire and there are flames in them still. During the day shadows seem to creep back with a shiver, as if afraid of them. Plato's Cave is up there." –

The painting above is a Cezanne oil of Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from the hill of Les Lauves, held in a private collection. This was one of his last paintings of the mountain, and indeed he came to this view late, but once he found it stuck to it as a loyal dog sticks to its owner. It was as if his whole life had been an ascent of this hill of Les Lauves on the outskirts of Aix-en-Provence, an ascent out of Plato's Cave into the Realm of Transcendental Forms. One time when I was sitting at this site in a kind of informal meditation upon the Form, an Aixoise local walked up to me and initiated a conversation – it turned out that, in all his thirty years living in this city, he had never before this occasion climbed this hill and seen this view. Needless to say, I marvelled greatly at this, then even more when after a mere minute or so he turned and walked back down. Cezanne in his late years called the locals imbeciles; I wouldn't be so harsh. We often seem to miss the grand things on our own doorsteps.

Cats are great teachers…stop moving, freeze, and hold a posture….I, Anubis, [the "catlike hound"] lie with my back stretched out…with my back haunches pulling my spine back, which raises serpentine energy in my body. With my paws forward, I stare out through time and hold geometrical forms in space. –

My fondness for Cezanne's late Victoire paintings may be more to do with my own relationship with their subject than anything to do with their style. Style-wise, Cezanne is one of art's unique characters, though the unique style he developed – think Van Gogh with the passionate, shammanic spirals replaced by diligent little parallel strokes – is more delicately expressed in his works from a slightly earlier period. Going for such looseness is all very daring, but generally speaking give me French Constantin or English Constable.

But I want to cast aside issues of style and personal preference, because the point is that I do feel a fondness for these particular images of his – the dozen or so oils of Sainte-Victoire all from this same viewing point – in part because like Cezanne I've spent whole days myself seated at this spot. I have done so, however, because of something even Cezanne may very well not have noticed. My times at Les Lauves have been spent pondering a great mystery.

Sainte-Victoire as Category 2 Sacred Site : the Carving

The big mystery concerns not simply the leonine profile that is visible from this perspective, but something else, something which appears to be of manmade provenance, and has yet drunk in the rich evening wine of three billion sunsets. I'll take you back now to the moment when this first became apparent to me.

The previous day I had read the delightful concluding part of Paulo Coelho's wonderful super-selling novel about an Andalucían shepherd, The Alchemist, a story that encourages us to journey into life's great adventures by paying attention to serendipitous omens. Like old Don Quixote, I had been affected by reading this romance, but not in a way that made me want to put on a war helmet and joust with giants. Coelho's book is about fulfilling one's Soul's desire or Personal Legend, which in the case of its protagonist, the Andalucían shepherd Santiago, involves a journey to see the Great Pyramids of Egypt. Later that day, during a road trip to San Tropez, Mont Sainte-Victoire (which at that time I had never heard of) was pointed out to me as being famous because of something to do with Cezanne. So when, the next day, I opened up an English magazine about France in general in the middle and saw there a double page spread devoted to the mountain and the artist, it seemed to me like just such a significant coincidence. The coincidence itself was not the most extraordinary, but I was primed to take note of even the more subtle signs. If you've never heard of something, then suddenly you hear about it more than once from sources not connected by basic causality, prick up thine ears. So anyway, apt for adventure with ears up-pricked, I surveyed the photos in this magazine article and the general sphinx-like profile was immediately obvious. Then for some reason – whether due to an inner prompting or just plain good luck – it seemed that looking for more evidence of this leonine epiphany beyond the simple outline would be quite natural, yet I must have really felt that I was doing this on the most outside off-chance, just playing, because when I actually saw what I was looking for I felt a tingling mixture of deep surprise, delight, bewilderment, awe and fascination:-

Right at the part of the simulacrum where the face should be I saw, smiling knowingly back at me… the regal delineations a lion's face.

Was this common knowledge? Why didn't the article mention it? Was it a case of one of those things that people haven't noticed, despite it being openly visible, simply because it is so far beyond what they expect to see? Were these lines formed from bushes randomly spaced, or were there actual cuts into the rock? And, Alchemist message taken on board and still influencing me, some part of me wondered perhaps a little quixotically whether I should also ask: was the rediscovery and revelation of this treasure part of my own "Personal Legend"?

I began an intense period of research, which did turn up the odd passing mention of the lion profile, but nowhere was the lion face spoken of. This, I decided, was left for me to do. If the lines were produced by cuts into the rock, I knew that the face took the mountain from Devereux's Category 1 sacred site – the recognisable natural form – to Category 2 – one enhanced by human action. Soon I would realise it was also an ideal Category 3 sacred site.

Going closer here in the image below we lose the desired angle, so the face is less clear (the eye indentation in particular being less clear), but what is definitely clarified is that we are not talking about a few randomly placed bushes just happening to cast the simulacra of a lion's face from a distance, but rather we are dealing with an actual cut into the rock. It can be seen here that the line of the mouth forms a well-defined ledge quite distinct from the lighter pocks on the surrounding rock face.

An archaeologist with knowledge of rock working who was also a capable rock climber might be able to shed light on the question of whether this is just an astounding coincidence – simulacra upon simulacra – or whether, as seems far more likely to me, it is the result of human action, that is if the 15,000 years of rain and ice have not removed all traces of such evidence. Either way, the image of the lion face is simply there.

If, as seems to me to be the case, this is a human-made enhancement, then for the reasons I've presented already the Magdalenians are, as far as I'm concerned, the most likely sculptors. If so, then we can only marvel at the daring and skill involved, the herculean commitment, the sheer creative genius of the concept, and the wisdom, from the Hermetic point of view, the alchemy of place. As an art historian will quickly tell you, perception of works of art is embedded in culture. Strip away all modernity and imagine how the hunter-gatherer people of the Lost Civilization saw this, then translate it back to the modern age, and the result has all the majesty of Atlantis.

And if it's just natural erosion, even then this would seem to be a coincidence with something transcendent about it.

Sainte-Victoire as Category 3 Sacred Site : The Return of Aslan

Wrong will be right when Aslan comes in sight

At the sound of his roar, sorrows will be no more

When he bares his teeth, winter meets its death,

And when he shakes his mane, we shall have spring again. –

"Mythopoetic" is an alternative form of "mythopoeic", a word coined from Greek roots meaning "the making of a new myth." Tolkein coined the term to describe the mythological mixtures used in his fantasy novels, and his friend from the Oxford University English department, C.S.Lewis, produced a fine example with his Narnia Chronicles, which have now sold over 100 million copies worldwide. Truly, a myth has been made, solidified in the collective realm of mythic space by its own strong collective morphic fields. The great hero of these chronicles is the mighty and benevolent lion Aslan. This golden, warm, giant flying feline brings the Spring, casting off the cold times of the Ice Queen. The Magdalenian culture flourished in the period during which the last major ice age gradually ended and the Earth warmed up. Narnia is a mishmash of mythologies, combining for example Greek and Roman mythological figures such as centaurs and fauns with elements of Celtic legend. As mentioned above, we know from their cave art that half-animal half-man figures were part of the Magdalenian imaginative (and/or shamanic) scope, figures that would not have been out of place in Narnia. And in subsequent history Provence has witnessed the comings and goings of Celts, Greeks and Romans, again making the Narnian mishmash rather appropriate.

"Mythopoetic" is now used in alternative history/Earth Mysteries/re-enchanting-the-land circles to communicate that a particular speculation, while it may indeed conceivably be historically correct, is to be considered not so much just from the rational, historical perspective, but more from poetic, mystical, multidimensional angles which provide it with a different kind of validity.

With such mythopoetic open-mindedness we may continue with increasing curiosity, for Plato has the dominion of the Atlantean kingdoms stretching west along the Med coast during the Late Magdalenian period from Iberia into Italy, and this area does indeed include Provence, while the commonality of artistic tradition exhibited by the Cave Painters across a wide area indicates that there was indeed some kind of grand organisation to the culture, perhaps centrally orchestrated. (Settagast, Plato Prehistorian.) Settagast refrains from actually calling the Magdalenians "Atlanteans", but does use the implicit term "Atlantics", which is justified by their homelands being in Western Europe.

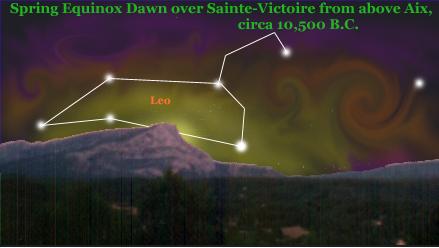

By Plato's timing Atlantis was a majestic culture during the Age of Leo, namely when the Sun was in the constellation of Leo during the Spring Equinox, Aslan ending the reign of the Ice Queen, and now we are warming to our mythopoetic scenario. Recall that it is while facing due east from Aix that we see the leonine profile. From other directions, the profile is very different. You only have to go a little way north or south and the lion disappears. It is an East-specific appearance. Also, the orientation is the same as the constellation figure – the lion in the East faces south, with tail to the north. Leo lies crouched on its front, just like Mont Sainte-Victoire seen looking East from the hill above Aix. Sky and Earth were in alignment as the Sun rose due east in Leo at Spring, the time of year when the ice melts…the Return of Aslan. And now as we edge into the Age of Aquarius, again there is an equinox alignment. Leo houses the Sun due east at sunrise at the Autumn Equinox during the Age of Aquarius while the grapes are fully ripened in the vineyards. The wardrobe of the Narnia stories starts to look like a time-portal into that former age, Aquarius back to Leo.

Actually, if we look at sources such as Ovid’s Fasti we find that the timing of sacred rites connected with particular constellations was often arranged to coincide not with the rise of the constellation at dawn while containing, and thus obliterated by the light of the Sun, but rather at a time when that constellation became visible again in the evening sky. These were the constellations that made an impression during a particular month. While the hardworking farmer might be up early to attend to his chores, the timing with the evening appearance makes greater sense to societies of late risers, which includes not only city dwellers, but also, one assumes, pre-agricultural hunter-gatherers. And when we consider it like this, it is the Age of Aquarius, into which we are currently emerging, in which the Lion of the sky is seen rising due east, just after sunset, aligned with the Aix mountain simulacra.

"It is always from the East, from across the sea, that the great Lion comes to us." –

In this poetically speculative theory, we then trace the Atlantean migration to and settlement of the Nile when Europe got cold again during the mini ice age of the Younger Dryas, with the Sphinx being carved in Egypt around that time simply because of a longing for the great Dreamtime totem of the land they left behind, because they wept at parting with the custodian of the imprint of their ancestors and the genius of the stellar lion.

In the special learning process of initiation, boys are often taken to sacred places which are often secret places. Their sacredness is sometimes marked by art of one form or another, whether portable objects, stone or earth arrangements or rock pictures….A Ngarinyin elder says: "I take the Mandangarri boy to the place. I say, this is your totem: you belong here." –

The mythopoetic way of describing this treasure is fabulous fuel for the sense of wonder : a majestic Atlantean leonine sculpture on a shining Mediterranean mountain, sphinx-like in perspective looking East, resonates with the stars and holds the keys of activation of the Hall of Records: the perceptual treasures and culture codes of the lost antediluvian civilization.

Simulacra in Antiquity and the Renaissance

In antiquity we find Roman writers such as Pliny and Cicero describing the way that Nature can create simulacra, such as the image of Silenus or of the god Pan in a block of marble. Later, in the formative years of the Renaissance, Alberti wrote that "it is evident that Nature herself delights in painting, for we observe She often fashions in marble hippocentaurs and bearded faces of kings." In his De Statua Alberti wrote of how man's image making itself has its origins in our observation of such images in the shapes of trees and other natural forms. It was quite possibly under the influence of Alberti that the painter Mantegna introduced obvious simulacra in the clouds in his studiolo painting for Isabella d'Este, Virtue Expelling the Vices, where we see the faces of gods, and the image of a rider on a horse also from the shapes of clouds in his St. Sebastian.

Details of clouds in Mantegna's St. Sebastian(left) and Virtue Expelling the Vices (right)

Titian visited Mantua and viewed Mantegna's paintings in 1519 so we should not be too surprised to find a similar mystery which may lurk in part of his own work, though the difference here may be that as far as I know it has not previously been recognized.

The painting is Bellini's Feast of the Gods. Although the original painting was by Bellini from a few years before Titian was brought into the project, it was later brought more into line with the other paintings in Alfonso d'Este's Alabaster Chamber by the younger painter Titian, who painted the new background with the rocky mountain, which in fact continues the sloping horizon from The Andrians which hung to its left. Looking at this feature which Titian added to the painting, it occurs to me that there may in fact be a simulacrum of a face in profile, and it further seems to me possible that this is Titian's sneaky way of getting a self-portrait into the frame. Note the similarity to his self-portrait here shown to the right.

I believe I may have uncovered another example of this type of subtle inclusion, to be found in a work by a classical painter of the following century. As Peter Humfrey's text in The Age of Titian tells us, Nicholas Poussin "is known to have made a close study of the Ferrara Bacchanals." Humpfrey notes that "his own Bacchanal with the Guitar Player…is manifestly inspired as much by Bellini's The Feast of the Gods [just discussed above] as by Titian's three bacchanals [which hung next to it], and the figure of the river god on the left is directly borrowed from Bellini's Mercury." As Humphrey notes, there is even a close copy of the Feast painting which may have been painted by Poussin.

So if he had noticed the face while copying the Bellini, he may well have thought about putting something similar into one of his own paintings.

Kate and I are now in Paris. It's sweltering, and Kate has already paddled in the pools outside the Louvre Pyramid in an attempt to cool down, and now we've descended below the glass pyramid and have entered the museum's Sully wing. We have a train to catch that evening, so this can't be a long visit. Mainly, we want to take a look at Poussin's Et In Arcadia Ego painting, the one that Granet placed on the walls above Poussin's deathbed, as discussed earlier, because I think I've noticed something, another possible simulacrum..

This one is quite faint, but the strength of my assertion rests on the back-story. The first two Et In Arcadia paintings, the original by Guercino, and also Poussin's own first version, both feature skulls being contemplated by the shepherds. In the Poussin the skull is located on top of the tomb.

Detail showing skull on tomb in Poussin's Shepherds of Arcadia I

This skull was a truly central feature of these paintings. Contemplation of a skull was linked to the melancholic humour of Saturn, the god who had ruled heaven in the Golden Age when the goddess Justice (Astraea) had not yet left the Earth and escaped to the stars. The Arcadian shepherds are envisaged as living in this Golden Age. This humour, melancholia, when it "catches fire", was in turn linked in the De Occulta Philosophia of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (following on from the ideas of Ficino of the Florentine Academy) to the ability to prophesy of the coming of figures like Christ as in Eclogue IV (where there is a prophesy about the birth of a divine child). Agrippa published as early as 1531, a century before the Et In Arcadia paintings. But though the feature was central to the first two Et In Arcadia paintings, there is no skull in the third, Poussin's Shepherds of Arcadia II¸ which is strange. Until we take a closer look.

We wend our way towards the French paintings section. Poussin chose Rome as his home but there is no doubt that the French view him as their own. We get sidetracked by an awesome room of ancient statues – the famous hermaphrodite, a centaur, satyrs, a silenus, a maenad, various Venuses and statues of Hermes. Then we see the Venus de Milo in a corridor and are drawn to her like a magnet. Eventually we tear ourselves away and go upstairs to the rooms of French painting. Kate and I manage to lose each other for a while, during which time I happen upon the Titian-influenced Poussin painting mentioned above, the Bacchanal with the Guitar Player, as well as the one we've come to see, The Shepherds of Arcadia II. I'm able to get up really close to have a proper look. Hmmm…I think it's there. Yes, it's there, surely.

Look at this close-up below of the mountain peak behind the tomb. There in the formation of the rock is the simulacrum of a skull-like head, looking to the left, as with the original, and similarly above the tomb, with perspective subtracted. There is the dome-like top of the head, the shadow of the eye socket, the hollow of the cheek below it, a hint of a mouth with the chin below. I don't know if anyone has noticed this before, but I've not read of it.

Skull above Tomb in Second Shepherds After All?

Jerusalem had its Golgotha, the "Place of the Skull", and the return of the Golden Age was linked to the realisation of the New Jerusalem. Rome of course had its Capitoline hill (Capital means head), and the gods such as Pan who had been Et In Arcadia had according to Ovid in his Fasti been transferred to Rome by the mythical Arcadian settler of early Rome, Evander, since which time were held there "the rites of two-horned Faunus." Even London has its association between the "White Hill" and the head of the Brythonic landscape giant Bran, the "Wondrous Head" which had caused a fabulous enchantment and transcending of mundane time upon a group that had sat in contemplation of it.

I bump into Kate again and drag her to have a look. She looks closely, but is not so sure. My conviction is shaken; perhaps it's just a coincidence, I wonder. Either way, our chief interest here has been, by intriguing coincidence, the actual mountain that Granet believed was the one that I think Poussin gave this skull-like face – Sainte-Victoire, the mountain of Aix.

I get the photo, and we continue through the Louvre. The Mona Lisa gives us a second goal (I've never seen her in the flesh), but I'm overwhelmed by the wealth of treasures along the way. We flit past Botticelli's, Mantegna's and Rafael's, then I'm stunned by the sheer size of Veronese's Wedding at Cana taking up an entire wall. Mona, at the opposite end of the great room, is a mere fraction of the size, but she still manages to hold centre stage for her great crowd of adoring pilgrims.

"What interests me about that is the continuing power that art has over people," says Kate, indicating the vast crowd looking at this small painting.

Picasso was right. Nothing's changed. We still seek out our sacred icons.

William Glyn-Jones